Saturday Gardening Thread: Bi-Polar Edition [Y-not and KT]

Y-not: Good afternoon, gardening morons and moronettes! Weirddave is indisposed so today's thread is a bi-polar edition featuring self and KT.

To get us in the mood, how about a song?

(You can read IZ's story here.)

The emergence of Spring coupled with those last few winter storms that are still hitting parts of the U.S. got me thinking about weather prediction, particularly almanacs. I have a feeling we have experts on this topic in our midst, so I'll just put together a few interesting links I found and let you all share your knowledge with the horde.

What is an almanac, anyway? Here's a brief summary from Mental Floss:

Historically, almanacs are annual publications that outline the days of the year alongside factors like sunrise and sunset times, holidays, moon phases, and solstices. The calendar hanging on your wall is an example of a simple almanac. Some of the earliest almanacs referenced celestial events to tell readers whether they would have good or bad luck on certain days, much like how we use horoscopes today. By the 17th century, the only publication more popular than almanacs in England was the Bible. Around this time, they began popping up in the America colonies, offering seasonal weather predictions, tips for household management, and entertainment like puzzles and jokes.The Farmers' Almanac (founded in 1818 ) and the Old Farmers' Almanac (founded in 1792) are two of the most popular remaining almanacs. The former offers long-range weather predictions made two years in advance. Today it claims to have an annual distribution of more than 2.6 million copies and a readership of 7 million.

Both publications claim to have a roughly 80 percent accuracy rate. Their predictions are the products of top secret mathematical formulas that take into consideration things like sunspot activity, tidal action, and planetary positioning

For those of you who use Almanacs, especially for your garden planning, do you think this 80 percent accuracy rate is correct?

An article published at the Daily Beast last month claims that the harsh New England winter was predicted correctly by The Farmers' Almanac:

Not only did they get it right, just as they claim to around 85 percent of the time -- they actually made this winter's predictions almost two years ago, using much the same technique they did back in the 1800s."It's like an ancient Chinese secret," says the Almanac's managing editor, Sandi Duncan gravely, before laughing. "No, I'm kidding. It is an old, old formula that dates back to when the Almanac was first founded back in 1818, it's a mathematical and astronomical formula. It takes things like sun spot activity, position of the moon, the phase of the moon, and a variety of other factors into consideration."

Even Duncan doesn't know the details, which are passed on only to the venerable publication's resident weatherman, Caleb Weatherbee, a shady, pseudonymous fellow who has had a byline in the book for two centuries.

"He's a real person, but he has a false name to keep him secret," Duncan explained. "We've only had seven weather prognosticators actually, in almost 200 years..."

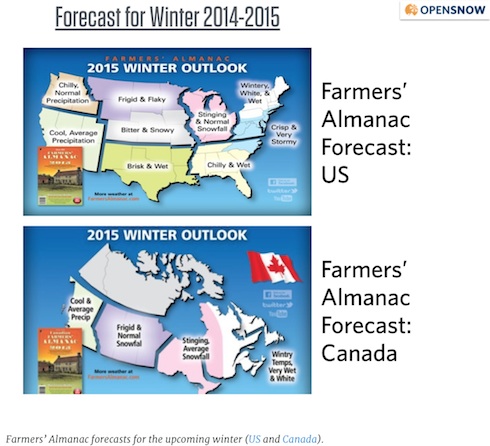

This chap at OPENSNOW seems less impressed. His analysis (published last year) suggested that neither almanac was particularly accurate. Here's his summary of the Farmers' Almanac's predictions for this past winter (which would have been in the future when his post was written):

Follow the link for pretty maps of his analysis. (I knew that would appeal to the horde after Meatball's Map Fests!)

If you're interested in learning more about how and why almanacs developed, this blog might be of interest to you. Here's a sample:

Almanac. Or Almanack. Or even Almanach. It doesn't matter how you spell it, we don't know for sure where the word comes from. The al bit at the beginning would point to an Arabic etymology -- it means the -- as in algebra, alcohol or alchemy. The latter part of the word could come from menakh, and al-menakh appears in Pedro de Alcala's Arabic-Castilian Vocabulista (1505), referring to the climate, with manah (probably intended as the same word) as a word for a sundial, but the word isn't found elsewhere in Arabic. Walter Skeat, in his Concise Etymological Dictionary (1882), is unequivocal that the word has no connection with Arabic whatsoever.

You-Know-Who will be crushed to learn that. Heh.

He goes on:

The first use of the word appears in Latin, in Roger Bacon's Opus Majus (1267), where he mentions ancient astronomers discussing tables that are called almanacs -

"In expositione tabularum, quae almanac vocantur."

Follow the link to this blogger's post and you'll be treated to interesting history, as well as beautiful images of ancient almanacs.

Closer to home, there are three almanacs that are probably most familiar to American gardeners: Poor Richard's Almanac, the Old Farmers' Almanac, and the Farmers' Almanac.

Poor Richard's Almanac was the brainchild of Benjamin Franklin:

After The Pennsylvania Gazette, Poor Richard was the most profitable enterprise that Franklin undertook as a publisher. It sold about 10,000 copies a year. Given the now indissoluble connection between "Poor Richard" and Benjamin Franklin, it should be emphasized that most of the material in Poor Richard was not actually written by Franklin. This was especially true of the aphorisms, their most famous feature. Franklin could have had no idea that the brief sayings he used, taken from "many Ages and Nations," would become the primary basis for his international fame as an author. He never pretended they were his own. He wrote in Poor Richard for 1746,"I know as well as thee, that I am no poet born; and it is a trade I never learnt, nor indeed could learn. . . .Why then should I give my readers bad lines of my own, when good ones of other people's are so plenty? 'Tis methinks a poor excuse for the bad entertainment of guests, that the food we set before them, though coarse and ordinary, is of one's own raising, off one's own plantation, etc. when there is plenty of what is ten times better, to be had in the market."

Intellectual property, the ownership of ideas, was not what mattered. The point was not where the ideas had come from but the uses to which they could be put.

The Old Farmer's Almanac was originally published in 1792.

Under the guiding hand of its first editor, Robert B. Thomas, the premiere issue of The Old Farmer's Almanac was published in 1792 during George Washington's first term as president. Although many other almanacs were being published at that time, Thomas's upstart almanac became an immediate success. In fact, by the second year, circulation had tripled from 3,000 to 9,000. Back then, the Almanac cost only six pence (about nine cents).An almanac, by definition, records and predicts astronomical events (the rising and setting of the Sun, for instance), tides, weather, and other phenomena with respect to time. So what made The Old Farmer's Almanac different from the others? Since his format wasn't novel, we can only surmise that Thomas's astronomical and weather predictions were more accurate, the advice more useful, and the features more entertaining.

Another well-known almanac in the U.S. is the Farmers' Almanac. A bit about it here:

The Farmers' Almanac weather predictions are based on a secret mathematical and astronomical formula. Developed in 1818 by David Young, the Almanac's first editor, this formula takes many factors into consideration, including sunspot activity, moon phases, tidal action, and more. This carefully guarded formula has been passed along from calculator to calculator and has never been revealed.

Finally, while reading up on almanacs, I was reminded of just how amazing our ancestors were. Do you remember learning about Benjamin Banneker when you were in school?

Astronomer. Entirely self-educated, Benjamin Banneker was born November 9, 1731, in Ellicott's Mills, Maryland. He was the son of an ex-slave named Robert, whose wife, Mary Banneky, was the daughter of an Englishwoman and an African ex-slave.Because both of his parents were free, Benjamin escaped the wrath of slavery as well. He was taught to read by his white grandmother, Molly, and for a short time attended a small Quaker school.

For the most part, though, Banneker was self-educated, a fact that did little to diminish his brilliance. His early exploits included constructing a wooden clock in his early twenties, despite having seen only one other timepiece in his life. In addition, Banneker taught himself astronomy and accurately forecasted lunar and solar eclipses.

Banneker's talents and intelligence eventually came to the attention of the Ellicott brothers, industrialists who had made their name and fortune by building a series of gristmills in the Baltimore area in the 1770s. George Ellicott, a fellow mathematician and astronomer, loaned Banneker numerous books in both fields.

In 1791 Banneker teamed up with Major Andrew Ellicott, an American surveyor, to map out a new national capital.

He also wrote almanacs.

Now, here's KT:

Weed of the Week

I hate grasses like these. They are so dangerous to pets - dogs in particular - and to livestock. Like a government program, the seed heads just work themselves in deeper over time. Plus, those nasty seed heads get stuck in your socks.

This list of nasty grasses is for California, but there are similar species in other parts of the country. You know that if a grass is called "ripgut", it must be pretty horrible. These grasses are more problematic for people on the edge of civilization, like we are, than for those in the Big City. But check your dogs after walks in slightly wilder areas.

Years ago, one of our dogs got a foxtail seed head in her paw, and it traveled almost to her knee before wreaking more havoc on a partial return trip down her leg. We had little clue that there was something wrong until just before we took her to the vet. Dogs are tough. When he saw how she was standing, he said, "I didn't know you lived in the country".

This year, I think we have cleared the yard where the dogs play. Still working on the yard where the cats play. Gotta hurry, because the seed heads are ripening now.

I hope the topic below is more pleasant:

Beefsteak Tomatoes

We had a couple of really hot, summery afternoons here recently that made me think it was time to be eating tomatoes from the garden. The hottest days came about the time that the birthday of Benito Juarez was being celebrated in Mexico, one of the first places where tomatoes were used as food. Juarez was unusual among historic Mexican leaders for his indigenous ancestry. He was born in a small Zapotec Indian village.

His ancestors may have eaten tomatoes something like the Zapotec Tomato (AKA Zapotec Pink Ribbed). A lot of people like this tomato for salsa, salads or for stuffed tomatoes. It is partially hollow. The stuffing tomatoes shaped like bell peppers never appealed to me much, but I might try Zapotec sometime. Here's a simple stuffed tomato recipe if you ever decide to try this cultivar. You could use regular tomatoes in this recipe, too.

Tomatoes have changed since old cultivars like the Zapotec Tomato were developed. But you can see traces of its form in some famous Italian cultivars and in some of today's beefsteaks.

When some people think of beefsteak tomatoes, they think of tomatoes big enough to cover a sandwich with one slice. And many beefsteaks are big enough to meet this criterion. But for me, the small seed cavities of a beefsteak tomato are the primary "beefsteak" characteristic. This makes the tomato less juicy, so it is not quite as messy on a sandwich. "Fine Cooking" has some good tips on choosing and storing beefsteak tomatoes. They also have a fairly extravagant recipe for a BLT Burger. I can enjoy a simple tomato sandwich - a slice of beefsteak tomato on good bread, with a little salt. Maybe a touch of butter. Maybe some bacon.

Note the small, irregular seed cavities in Giant Belgium, below. An advantage if you're making sandwiches.

Some of the Neves Azorean Red tomatoes above look better suited to salad than sandwiches, because of their shape. I'm with James Beard - keep a beefsteak tomato and onion steakhouse salad simple. You can't beat ingredients straight from the garden. In Switzerland, they would arrange the tomatoes on a platter and top with the onions and vinaigrette.

The unpredictable shapes of many beefsteak tomatoes come partly from big, complex blossoms. There are some unfortunate consequences of these irregularities in many cultivars, including cracking (usually starting at the shoulder of the fruit) and catfacing on the blossom end. Tomato nuts who care mostly about flavor generally look beyond the defects. You can't always judge veggies, or people, by their appearances.

Are you now asking yourself, "Are beefsteak tomatoes right for my garden"?

Tomato Growers Supply has separated most of its red and pink beefsteaks into a distinct category. The venerable hybrid "Big Beef", which I grow every year, is not in the beefsteak category. It is listed with the main crop tomatoes, because it does not have the interior structure of a beefsteak.

Other suppliers offer many more beefsteaks. Check out some descriptions and evaluations on the net from people who live in your region. I like to experiment with a few new cultivars each year. I planted 21 tomato cultivars this year. Eight are beefsteaks and one appears to be an oxheart/beefsteak cross. Only two of this year's eight beefsteaks have a prior good track record in my garden, and they were still not extraordinarily productive.

I'm not really up on some of the newer hybrid beefsteaks. Burpee has some huge ones now. Other seed houses have signature series, too. Let me know if they have worked for you.

Following are some recommendations I have picked up over the years. No guarantees:

Container Planting: New Big Dwarf (the inspiration for the Dwarf Tomato Project), Roselle Purple or Dwarf Wild Fred.

Short season or cool summer areas: Gregori's Altai, Pruden's Purple, Pink Berkeley Tie Dye, Soldacki, Goldie, Gold Medal, Chianti Rose, Bush Beefsteak F1 or New Big Dwarf.

Hot, dry areas (not the interior deserts, necessarily): Dr. Lyle and Stump of the World have done well for me. Others recommended for our area include Boondocks, Brandy Boy F1, Neves Azorean Red, Giant Belgium, Marianna's Peace, Jumbo Jim Orange or Mexico (not "Mexican Beefsteak").

Hot, humid areas: JD's Special C Tex, Indian Stripe, Dixiewine or Florida Pink. I know there are more.

Really big plants: Climbing Trip-L-Crop or Pink Climber.

Competitive tomato-growing: Last I heard, "Delicious" held the world record for the largest tomato - more than 7 pounds. Burpee introduced this cultivar in 1964 after years of selection from "Beefsteak" (AKA Crimson Cushion or Ponderosa Red). Delicious is reputed to hold its flavor when the nights turn cold in fall. This is probably a good thing, since it ripens late.

Other tomatoes promoted for competition include Big Zac F1, Goliath (open pollinated - not the hybrid lines) and Believe It or Not.

I was surprised to find a giant tomato contest in the UK, because they tend to grow tomatoes in greenhouses. A cash prize is involved. How long can Delicious hold the title in the face of international competition?

The article linked above has a side discussion on tomatoes resistant to "Blight" - known as "Late Blight" in the USA. This is the organism that produced the Irish Potato Famine. A few hybrid tomato cultivars carrying specific genes for resistance to this organism have now been introduced. Two were recently released through the University of North Carolina. A few heirlooms and other tomatoes have varying amounts of natural resistance. But if you live where tomato diseases are a big problem, hybrids with known resistance to the diseases in your area may be good "crop insurance". You may still want to baby an heirloom beefsteak plant for a chance to experience sublime flavor.

Y-not: Thanks, KT!

Speaking of Benjamin Franklin:

Benjamin Franklin is sometimes erroneously credited with the idea of Daylight Saving Time.Franklin discussed the idea of changing sleeping times in a 1784 satirical essay sent to the editor of the Journal of Paris.

"I looked at my watch, which goes very well, and found that it was but six o'clock; and still thinking it something extraordinary that the sun should rise so early, I looked into the almanac, where I found it to be the hour given for his rising on that day. I looked forward, too, and found he was to rise still earlier every day till towards the end of June; and that at no time in the year he retarded his rising so long as till eight o'clock. Your readers, who with me have never seen any signs of sunshine before noon, and seldom regard the astronomical part of the almanac, will be as much astonished as I was, when they hear of his rising so early; and especially when I assure them, that he gives light as soon as he rises. I am convinced of this. I am certain of my fact. One cannot be more certain of any fact. I saw it with my own eyes. And, having repeated this observation the three following mornings, I found always precisely the same result."

According to WebExhibits.org, Franklin thought the switchover would be easy with "All the difficulty will be in the first two or three days; after which the reformation will be as natural and easy as the present irregularity."

According to Franklin, if people were to rise an hour earlier, they would willingly go to bed an hour earlier in order to compensate. He also said the citizens of France could save the modern-day equivalent of $200 million on candles because as many wouldn't be needed if people slept when it was dark and awoke when it was light. He even worked out the math.

Well, everyone makes mistakes!

What's going on in YOUR gardens this week?