Intermarkets' Privacy Policy

Support

Donate to Ace of Spades HQ!

Contact

Ace:aceofspadeshq at gee mail.com

Buck:

buck.throckmorton at protonmail.com

CBD:

cbd at cutjibnewsletter.com

joe mannix:

mannix2024 at proton.me

MisHum:

petmorons at gee mail.com

J.J. Sefton:

sefton at cutjibnewsletter.com

Recent Entries

Antifa-Affiliated Group Stomps a Normal Peaceful Student to Death in Lyon, France

Microsoft AI CEO: Most White-Collar Jobs Will be "Automated by AI" Within Ten Years

I Mean, Within Twelve to Eighteen Months

Stephen Colbert Involved in Yet Another Leftwing Propaganda Hoax

Jesse Jackson Departs This Mortal Coil to Shake-Down Heaven and Demand God Give $300,000 p.a. Jobs to His Retarded Cousins and Staffers

Palestinian Activist in NYC Calls for Dogs to be Banned as "Indoor Pets" -- No Longer Permitted Inside People's Private Apartments -- Because They are "Unislamic" and "Dirty"

Yet Another "Trans" Mass Shooting the Media Will Pretend Was Perpetrated by a "Woman"

Operation PROTECT DONKEY-CHOMPERS: Leftwing Propaganda Media Goes Into Overdrive Claiming That AOC's Embarrassingly Incompetent Performance At Munich Was Akshually "Cogent" and Critics Are Just "Microscopically Dissecting" Her "Message"

The Morning Rant

Mid-Morning Art Thread

The Morning Report — 2/17/26

Microsoft AI CEO: Most White-Collar Jobs Will be "Automated by AI" Within Ten Years

I Mean, Within Twelve to Eighteen Months

Stephen Colbert Involved in Yet Another Leftwing Propaganda Hoax

Jesse Jackson Departs This Mortal Coil to Shake-Down Heaven and Demand God Give $300,000 p.a. Jobs to His Retarded Cousins and Staffers

Palestinian Activist in NYC Calls for Dogs to be Banned as "Indoor Pets" -- No Longer Permitted Inside People's Private Apartments -- Because They are "Unislamic" and "Dirty"

Yet Another "Trans" Mass Shooting the Media Will Pretend Was Perpetrated by a "Woman"

Operation PROTECT DONKEY-CHOMPERS: Leftwing Propaganda Media Goes Into Overdrive Claiming That AOC's Embarrassingly Incompetent Performance At Munich Was Akshually "Cogent" and Critics Are Just "Microscopically Dissecting" Her "Message"

The Morning Rant

Mid-Morning Art Thread

The Morning Report — 2/17/26

Absent Friends

Jay Guevara 2025

Jim Sunk New Dawn 2025

Jewells45 2025

Bandersnatch 2024

GnuBreed 2024

Captain Hate 2023

moon_over_vermont 2023

westminsterdogshow 2023

Ann Wilson(Empire1) 2022

Dave In Texas 2022

Jesse in D.C. 2022

OregonMuse 2022

redc1c4 2021

Tami 2021

Chavez the Hugo 2020

Ibguy 2020

Rickl 2019

Joffen 2014

Jim Sunk New Dawn 2025

Jewells45 2025

Bandersnatch 2024

GnuBreed 2024

Captain Hate 2023

moon_over_vermont 2023

westminsterdogshow 2023

Ann Wilson(Empire1) 2022

Dave In Texas 2022

Jesse in D.C. 2022

OregonMuse 2022

redc1c4 2021

Tami 2021

Chavez the Hugo 2020

Ibguy 2020

Rickl 2019

Joffen 2014

AoSHQ Writers Group

A site for members of the Horde to post their stories seeking beta readers, editing help, brainstorming, and story ideas. Also to share links to potential publishing outlets, writing help sites, and videos posting tips to get published.

Contact OrangeEnt for info:

maildrop62 at proton dot me

maildrop62 at proton dot me

Cutting The Cord And Email Security

Moron Meet-Ups

« Hobby Thread - July 19, 2025 [TRex] |

Main

| Saturday Night "Club ONT" July 19, 2025 [The 3 Ds] »

Hyperbole has the opposite intended effect most of the time. We live in a saturated information age where anyone has a voice, and every voice wants to be heard. You don't get attention by saying something is pretty good. You have to be loud, and saying things are the greatest or worst things ever becomes ever-present, making each successive declaration less convincing than the last. So, when someone with a (tiny) voice discovers something they genuinely think may be one of the best ever, one must be careful, especially if that thing is fairly far removed from the audience's expectations.

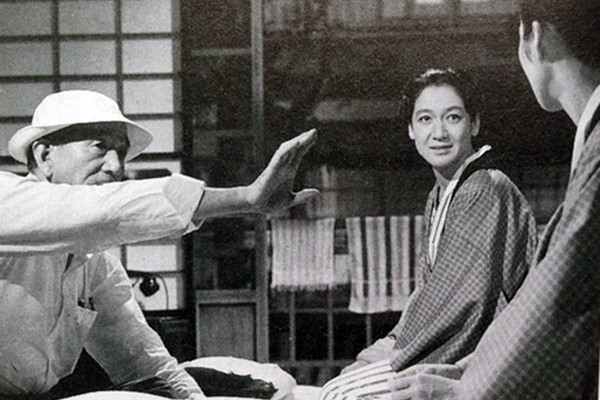

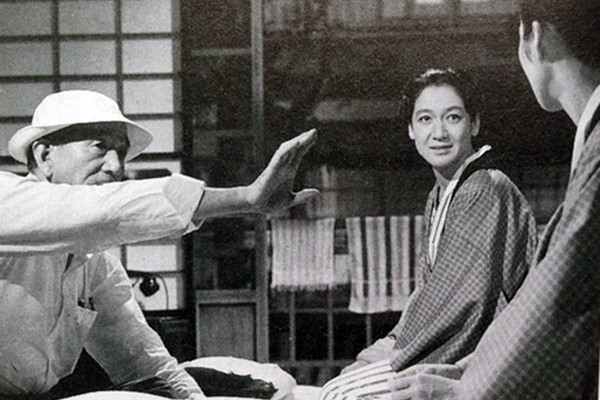

When considering the top-most tier of talent behind the camera of film history, one is met with titans. Akira Kurosawa. Charlie Chaplin. Martin Scorsese. Federico Fellini. Ingmar Bergman. Steven Spielberg. John Ford. Men who shaped the medium, made great art, and entertained millions. But sometimes, you encounter someone quieter, less assuming, and more refined (I use that word very specifically), and you realize that perhaps the greatest of them is someone fewer people take notice of.

Yasujiro Ozu was one of the earliest of Japanese feature filmmakers, beginning his filmmaking directing career in 1927 (in the American context, I would consider him second generation like Howard Hawks). By the time Akira Kurosawa was a young director, Ozu was a titan in the Japanese filmmaking world, able to override Imperial censorship objections of Kurosawa's The Men Who Tread on Tiger's Tails through simple praise of the work at the censorship meeting as recounted by Kurosawa in his (something like an) autobiography. He'd dominated the Japanese film world artistically for years, winning the Japanese equivalent of the Best Picture Oscar (the Kinema Junpo Award) a total of six times, including three years in a row (1932-1934).

And yet, his films are deceptively simple. Once he gained as full control as one can in the industry, roughly the mid-30s, he made, almost exclusively, quiet family dramas with little obvious visual flair. It was these kinds of movies that moved him from critical darling to box office champion in Japan. This was happening concurrently while the aforementioned Kurosawa was bringing Western filmmaking technique (and advancing it on his own) to action movies in the same country with movies like The Hidden Fortress and Yojimbo. And yet, Ozu's films were just as popular in Japan.

Now, books have been written about Ozu, his Zen influences, and his technique. One major reason I decided to dig into Ozu's work, of which I was passingly familiar beforehand, was reading Paul Schrader's Transcendental Style in Film, a largely academic work he wrote in his twenties that features Ozu prominently. I'm not going to dig into that stuff in any significant manner in this essay (though, I imagine an unwritten book to be had would be about the use of clothing). This is more of an introduction, an effort to get people unfamiliar with even his name to check him out. I think, though, that it's going to be a challenge.

Pacing is how quickly information and events happen in a story. Most of us have been conditioned through our entertainment choices to expect a certain, elevated pacing, a constant movement of plot to get to the next point. I think it's a key point of growth when we move beyond that to realize a simple truth: slower films can be engrossing, too.

In Paul Schrader's book, he also has a chapter on Robert Bresson, and the Criterion Collection interviewed Schrader for their home video release of Bresson's Pickpocket. In that interview, Schrader briefly touches on the idea of pacing, using an example of the main character passing through a door, how Bresson lingers too long before the character enters the shot and cuts too late, especially when the shot afterwards starts too early, to establish how Bresson uses pacing to affect something specific from his audience (unease, mostly). I mention it only because I can link to video easily and people will be more likely to click on it. (The below embed starts at 9:30 and where Schrader begins talking about pacing.)

Schrader also discusses pacing when writing about Ozu in his book, and it's something I remember Stephen Prince, the film scholar who taught at Virginia Tech, talking about when he taught Tokyo Story in his survey class. Ozu will start scenes with shots of empty rooms that will linger for a second or two before a character walks in. Scenes will end with characters walking out of a room and Ozu lingers on that empty room for a second before cutting to the next scene. Much like Bresson, there's a purpose to this, even if the purpose is very different. Ozu doesn't want to create distance or discomfort. He uses his pacing to do the exact opposite. Everything about how Ozu makes his films is about getting the audience settled into the reality of his films, and his pacing is about helping you feel like you are there, like you are sitting in the room as an observer, not filtering your view of the action through the choices of someone else (though this, of course, is a choice on his part which starts a rabbit hole I'm never going to go down).

However, there's another reason he does this, and it's introspection. His films never stop. They're always moving, but they're moving in small ways. Conversations occur where characters advance their little stories, by the end almost always about parents trying to marry off their adult daughter, and progressing from one action to the next (many key actions, like the meeting of characters, can happen off screen). However, after moments of drama, like an argument, he'll always go quiet so that people can reflect on what has just happened.

The example I keep coming back to comes from his film The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice, a story of a childless, middle-aged couple who invite their niece to join them for a short time. The niece, observing the relationship and finding it unfair to her uncle, stirs things up which brings out some simmering issues between man and wife. Near the end of the film, after an argument where the uncle lists how his wife henpecks him about everything (including the titular spilling of sauces over rice which she considers gauche and provincial) they stop talking. Instead, they decide that it's time for a late-night snack. So, Ozu, mostly in one wide-shot of their kitchen, watches as the pair bring plates and bowls out of cupboards, placing them on a tray, and collecting their rice from their ohitsu, and then they bring it into their living room where they sit on the floor and begin to eat.

What was accomplished by this look at the mundane reality of collecting things for a late-night snack? Time was accomplished. Time for both characters and audience to reflect on the magnitude of what was said and realize that, despite the heat of the moment, it wasn't that important. That there was still love there, love we'd seen peek through the film, and giving them space to reconnect.

The slow and steady pacing of his films, of people largely calmly talking to each other in rooms, has this cumulative effect that define his films and make them work emotionally. They require patience, especially from the perspective of an American weened on American cinema of the last 50 years, but that patience is rewarded in the end.

Growth in the Industry

The one thing to keep in mind about Ozu is that he repeats himself a lot. The only other filmmaker I've explored who repeats themselves nearly this much was Howard Hawks who kept making movies about love triangles between two men in a dangerous profession and the woman who loved them both. With Ozu, whose career is largely defined by his post-WWII work, it's mostly about small family dramas. His career started differently, though.

All but three of his films were made with the same studio, Shochiku Films, and he was very much a studio director, especially in his silent period. From 1927 to 1935 he made thirty-three silent feature films (only thirteen of them are extant with one more only missing two reels), and he jumped from genre to genre. There were a lot of gangster movies, crime movies, and melodramas. It was here where he let most of his cinematic influences fly the most freely, especially the works of Alfred Hitchcock (evidenced with heavy shadow work like in That Night's Wife) or Ernst Lubitsch (like the style of comedy in The Lady and the Beard), but through it all, knowing what's to come, it's easy to see Ozu exerting himself over his films to bend them to what he naturally wanted to do through the art of cinema. So, take the crime example of That Night's Wife, the story of a man who robs a bank to pay for medicine for his sick daughter, followed by home by a policeman, and most of the film is people kind of just staring at each other as they wait out the night to see if she gets better (there's some exchanges of ownership of a gun to help keep the tension up). That whole backend of the film in one room feels very Ozu in a crime film context.

And he was greatly respected in the film industry for what he did. It took some time until he met consistent commercial success (I've read that his first "box office success" was Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, which came out in 1941, something I can't really verify because I can't find box office returns for Japan in the 1930s and 40s), but it was obvious that he was using his growing influence to tell stories he wanted to tell, and those trended towards the family drama.

By the time WWII was over, though, the Imperial Japanese censorship regime was dead, replaced by an American occupation censorship regime, and Ozu's brand of small, family drama fit in well with the American propaganda concerns in the nation (one of Kurosawa's films of this period, No Regrets for Our Youth, is all about how militarism is bad and farming is good). It was the perfect period for Ozu to use his clout within the industry to make the films he wanted.

Refinement

And he wanted to make one movie. He wanted to make it over and over again. It was the story of a widowed parent trying to convince his or her adult daughter to marry and move out of the house. There were definite exceptions (mostly when he would loan himself out to other studios, Shintoho for The Munekata Sisters, an adaptation of a melodramatic book, Daiei for Floating Weeds, a remake of his own silent A Story of Floating Weeds, and Toho for The End of Summer, an excuse to work with as many Toho regulars as possible). And, of course, his most famous film, Tokyo Story, isn't about it. However, Late Spring, Early Summer, Equinox Flower, Late Autumn, and An Autumn Afternoon are all about parents trying to marry off their daughters.

And that kind of repetition can often be dismissed by people. Why doesn't he do something new? I remember this being hurled at Wes Anderson right about the time that The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou came out, stylistically extremely similar to The Royal Tenenbaums, and I found it curious. I enjoyed both films, even if they were stylistically very similar with thematic concerns around daddy-issues. Wasn't the point that the films were good? That was the point for Ozu.

And so he created his own personal music box, "a little box where the same actors play the same characters, playing the same plots over and over again. Comfortable, yet emotionally involving," as Mark Andrew Edwards put it, who went along for most of the journey with me. And it works. The gentle way he could create characters, elide the biggest events and focus on the smaller build ups and aftereffects, all while quietly inviting the audience to just sit down on the tatami mat like a family member creates this world of a not quite real Tokyo, too nice to be reality, but full of true human emotions that are there for those willing to sit on that tatami.

And I think you should.

Sitting Down on the Tatami

So, imagine for a moment that I've intrigued you. Where do you begin? Start with his most famous film, Tokyo Story. The story of two elderly parents who try and spend a week with their two children and their deceased son's wife in the eponymous city, getting shuffled around because life happens, never really connecting with their children but being understanding about it the whole time. It's a marvelous film, but you have to be ready for the rhythms of Ozu's cinematic grammar.

And that's why I start with such hesitation. How many will say, "Sure, I'll try this," see a five-minute long scene of two old people packing, and just be turned off because "nothing's happening"? I wish I had the authority to just say, "Watch this," and people would be patient with whatever I recommended, but that's not the case. You're more likely to dismiss my recommendations blind than accept them, so I gingerly describe what Ozu's films are like, how they work, why they came about, and hope that those of you who read through and feel like there's something there in Ozu's work that interests you won't be surprised when you do finally try.

That's not going to be all of you. I doubt it's most of you. Heck, I doubt it's a significant portion of you. However, for those few of you who do think that Ozu's music boxes of repeating characters, actors, and plots sounds intriguing and have never discovered it, well...start with Tokyo Story. The whole thing is on archive.org for some reason. Also, my personal favorite Ozu film, Late Autumn, is also available on archive.org in full.

And for those interested in Schrader's take on Ozu, there's the book itself, Transcendental Style in Film, which you can find anywhere to buy, but there's also this 26-minute long video of him summarizing the new introduction he wrote a few years ago to the book he wrote in his youth in the early 70s. The book is an academic text, but I found it engrossing and interesting.

Another Voice

Mark Andrew Edwards decided to go along on this journey with me, watching as much of Ozu's filmography as he could, and he ended up writing an essay of his own. Mark and I don't always agree on movies, and there were Ozu films that we found some distance between ourselves on, but Ozu's films obviously ended up meaning something to him as well. So, I want to end with an observation from his essay (which you can read in full here):

"But we are in the room, an invisible ghost, a trusted friend of the family, allowed to see everything, knowing we aren't there to interfere, but just share and learn, maybe to commemorate, maybe to celebrate silently with them. And sometimes, we leave the characters and contemplate the natural world outside, drifting along with the wind memorably in one instance. His films aren't in a hurry to hustle us outside or on to the next spectacle. There's no big drama, just little dramas, of life. Life moving on. Ozu stories don't end, the camera is just turned off. All these characters are going on, living their life even after our observation ends."

Movies of Today

Opening in Theaters:

I Know What You Did Last Summer

Eddington

Smurfs

Movies I Saw This Fortnight:

Late Autumn (Rating 4/4) Full Review "The combination of light comedy and clear-eyed character work that drives the drama creates this emotional impact and catharsis by the end that carries me for the final half-hour. It's subtle, deeply moving, funny, a remarkable film. It's one of the greats." [The Criterion Channel]

The End of Summer (Rating 3/4) Full Review "So, it's good. Ozu was simply far too skilled at this point to make anything less than that. However, this feels like a film bred from something other than his desire to refine his technique, an attempt to take advantage of a unique professional situation rather than a story he needed to tell once more, though it does share a lot of the same motifs." [The Criterion Channel]

An Autumn Afternoon (Rating 4/4) Full Review "I loved this film. Absolutely loved it. If Late Autumn hadn't hit me so hard, I'd be calling this Ozu's best work in a body of work that includes Tokyo Story. And that's why I wanted Ozu to live and work another 30 years. He could make the same story of a parent giving away a daughter repeatedly forever, and I'd watch and enjoy them forever." [The Criterion Channel]

The Young Stranger (Rating 4/4) Full Review "It doesn't surprise me that no one searches out Frankenheimer's first film, a small family drama he made in the middle of his television career before Birdman of Alcatraz with no movie stars and not at all genre related. But, I think that should be fixed." [YouTube]

The Young Savages (Rating 2.5/4) Full Review "There's a lot to admire in the first two-thirds of the film. The last third, though, simply fumbles things uncompellingly with a combination of bad courtroom antics and intentional obfuscation." [Prime]

Birdman of Alcatraz (Rating 3/4) Full Review "It's how the film can never quite separate itself from the fact that it's almost as much an issue piece as it is a human interest piece. However, the human interest side wins out in the end. It's a nice, easy little fantasy about the strength of the human heart, and not much else." [YouTube]

Seven Days in May (Rating 4/4) Full Review "It exists in something of a fantasy world where the military would orchestrate a coup without the CIA, the USSR is remotely trustworthy, and a disarmament treaty had any chance at all of passing the Senate in the early 60s. Still, within that fantasy world, this is a banger of a thriller. Dr. Strangelove had a better handle on the real world situation, though." [Personal Collection]

The Train (Rating 4/4) Full Review "And that makes The Train a complete package of a film. Entertaining on the surface but thoughtful just underneath, expertly filmed and wonderfully performed, especially by Lancaster and Scofield, it's John Frankenheimer's greatest achievement." [Personal Collection]

Contact

Email any suggestions or questions to thejamesmadison.aos at symbol gmail dot com.

I've also archived all the old posts here, by request. I'll add new posts a week after they originally post at the HQ.

My next post will be on 8/9, and it will be about ___.

July 19, 2025

Saturday Evening Movie Thread - 7/19/2025

Yasujiro Ozu

Hyperbole has the opposite intended effect most of the time. We live in a saturated information age where anyone has a voice, and every voice wants to be heard. You don't get attention by saying something is pretty good. You have to be loud, and saying things are the greatest or worst things ever becomes ever-present, making each successive declaration less convincing than the last. So, when someone with a (tiny) voice discovers something they genuinely think may be one of the best ever, one must be careful, especially if that thing is fairly far removed from the audience's expectations.

When considering the top-most tier of talent behind the camera of film history, one is met with titans. Akira Kurosawa. Charlie Chaplin. Martin Scorsese. Federico Fellini. Ingmar Bergman. Steven Spielberg. John Ford. Men who shaped the medium, made great art, and entertained millions. But sometimes, you encounter someone quieter, less assuming, and more refined (I use that word very specifically), and you realize that perhaps the greatest of them is someone fewer people take notice of.

Yasujiro Ozu was one of the earliest of Japanese feature filmmakers, beginning his filmmaking directing career in 1927 (in the American context, I would consider him second generation like Howard Hawks). By the time Akira Kurosawa was a young director, Ozu was a titan in the Japanese filmmaking world, able to override Imperial censorship objections of Kurosawa's The Men Who Tread on Tiger's Tails through simple praise of the work at the censorship meeting as recounted by Kurosawa in his (something like an) autobiography. He'd dominated the Japanese film world artistically for years, winning the Japanese equivalent of the Best Picture Oscar (the Kinema Junpo Award) a total of six times, including three years in a row (1932-1934).

And yet, his films are deceptively simple. Once he gained as full control as one can in the industry, roughly the mid-30s, he made, almost exclusively, quiet family dramas with little obvious visual flair. It was these kinds of movies that moved him from critical darling to box office champion in Japan. This was happening concurrently while the aforementioned Kurosawa was bringing Western filmmaking technique (and advancing it on his own) to action movies in the same country with movies like The Hidden Fortress and Yojimbo. And yet, Ozu's films were just as popular in Japan.

Now, books have been written about Ozu, his Zen influences, and his technique. One major reason I decided to dig into Ozu's work, of which I was passingly familiar beforehand, was reading Paul Schrader's Transcendental Style in Film, a largely academic work he wrote in his twenties that features Ozu prominently. I'm not going to dig into that stuff in any significant manner in this essay (though, I imagine an unwritten book to be had would be about the use of clothing). This is more of an introduction, an effort to get people unfamiliar with even his name to check him out. I think, though, that it's going to be a challenge.

Pacing

Pacing is how quickly information and events happen in a story. Most of us have been conditioned through our entertainment choices to expect a certain, elevated pacing, a constant movement of plot to get to the next point. I think it's a key point of growth when we move beyond that to realize a simple truth: slower films can be engrossing, too.

In Paul Schrader's book, he also has a chapter on Robert Bresson, and the Criterion Collection interviewed Schrader for their home video release of Bresson's Pickpocket. In that interview, Schrader briefly touches on the idea of pacing, using an example of the main character passing through a door, how Bresson lingers too long before the character enters the shot and cuts too late, especially when the shot afterwards starts too early, to establish how Bresson uses pacing to affect something specific from his audience (unease, mostly). I mention it only because I can link to video easily and people will be more likely to click on it. (The below embed starts at 9:30 and where Schrader begins talking about pacing.)

Schrader also discusses pacing when writing about Ozu in his book, and it's something I remember Stephen Prince, the film scholar who taught at Virginia Tech, talking about when he taught Tokyo Story in his survey class. Ozu will start scenes with shots of empty rooms that will linger for a second or two before a character walks in. Scenes will end with characters walking out of a room and Ozu lingers on that empty room for a second before cutting to the next scene. Much like Bresson, there's a purpose to this, even if the purpose is very different. Ozu doesn't want to create distance or discomfort. He uses his pacing to do the exact opposite. Everything about how Ozu makes his films is about getting the audience settled into the reality of his films, and his pacing is about helping you feel like you are there, like you are sitting in the room as an observer, not filtering your view of the action through the choices of someone else (though this, of course, is a choice on his part which starts a rabbit hole I'm never going to go down).

However, there's another reason he does this, and it's introspection. His films never stop. They're always moving, but they're moving in small ways. Conversations occur where characters advance their little stories, by the end almost always about parents trying to marry off their adult daughter, and progressing from one action to the next (many key actions, like the meeting of characters, can happen off screen). However, after moments of drama, like an argument, he'll always go quiet so that people can reflect on what has just happened.

The example I keep coming back to comes from his film The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice, a story of a childless, middle-aged couple who invite their niece to join them for a short time. The niece, observing the relationship and finding it unfair to her uncle, stirs things up which brings out some simmering issues between man and wife. Near the end of the film, after an argument where the uncle lists how his wife henpecks him about everything (including the titular spilling of sauces over rice which she considers gauche and provincial) they stop talking. Instead, they decide that it's time for a late-night snack. So, Ozu, mostly in one wide-shot of their kitchen, watches as the pair bring plates and bowls out of cupboards, placing them on a tray, and collecting their rice from their ohitsu, and then they bring it into their living room where they sit on the floor and begin to eat.

What was accomplished by this look at the mundane reality of collecting things for a late-night snack? Time was accomplished. Time for both characters and audience to reflect on the magnitude of what was said and realize that, despite the heat of the moment, it wasn't that important. That there was still love there, love we'd seen peek through the film, and giving them space to reconnect.

The slow and steady pacing of his films, of people largely calmly talking to each other in rooms, has this cumulative effect that define his films and make them work emotionally. They require patience, especially from the perspective of an American weened on American cinema of the last 50 years, but that patience is rewarded in the end.

Growth in the Industry

The one thing to keep in mind about Ozu is that he repeats himself a lot. The only other filmmaker I've explored who repeats themselves nearly this much was Howard Hawks who kept making movies about love triangles between two men in a dangerous profession and the woman who loved them both. With Ozu, whose career is largely defined by his post-WWII work, it's mostly about small family dramas. His career started differently, though.

All but three of his films were made with the same studio, Shochiku Films, and he was very much a studio director, especially in his silent period. From 1927 to 1935 he made thirty-three silent feature films (only thirteen of them are extant with one more only missing two reels), and he jumped from genre to genre. There were a lot of gangster movies, crime movies, and melodramas. It was here where he let most of his cinematic influences fly the most freely, especially the works of Alfred Hitchcock (evidenced with heavy shadow work like in That Night's Wife) or Ernst Lubitsch (like the style of comedy in The Lady and the Beard), but through it all, knowing what's to come, it's easy to see Ozu exerting himself over his films to bend them to what he naturally wanted to do through the art of cinema. So, take the crime example of That Night's Wife, the story of a man who robs a bank to pay for medicine for his sick daughter, followed by home by a policeman, and most of the film is people kind of just staring at each other as they wait out the night to see if she gets better (there's some exchanges of ownership of a gun to help keep the tension up). That whole backend of the film in one room feels very Ozu in a crime film context.

And he was greatly respected in the film industry for what he did. It took some time until he met consistent commercial success (I've read that his first "box office success" was Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, which came out in 1941, something I can't really verify because I can't find box office returns for Japan in the 1930s and 40s), but it was obvious that he was using his growing influence to tell stories he wanted to tell, and those trended towards the family drama.

By the time WWII was over, though, the Imperial Japanese censorship regime was dead, replaced by an American occupation censorship regime, and Ozu's brand of small, family drama fit in well with the American propaganda concerns in the nation (one of Kurosawa's films of this period, No Regrets for Our Youth, is all about how militarism is bad and farming is good). It was the perfect period for Ozu to use his clout within the industry to make the films he wanted.

Refinement

And he wanted to make one movie. He wanted to make it over and over again. It was the story of a widowed parent trying to convince his or her adult daughter to marry and move out of the house. There were definite exceptions (mostly when he would loan himself out to other studios, Shintoho for The Munekata Sisters, an adaptation of a melodramatic book, Daiei for Floating Weeds, a remake of his own silent A Story of Floating Weeds, and Toho for The End of Summer, an excuse to work with as many Toho regulars as possible). And, of course, his most famous film, Tokyo Story, isn't about it. However, Late Spring, Early Summer, Equinox Flower, Late Autumn, and An Autumn Afternoon are all about parents trying to marry off their daughters.

And that kind of repetition can often be dismissed by people. Why doesn't he do something new? I remember this being hurled at Wes Anderson right about the time that The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou came out, stylistically extremely similar to The Royal Tenenbaums, and I found it curious. I enjoyed both films, even if they were stylistically very similar with thematic concerns around daddy-issues. Wasn't the point that the films were good? That was the point for Ozu.

And so he created his own personal music box, "a little box where the same actors play the same characters, playing the same plots over and over again. Comfortable, yet emotionally involving," as Mark Andrew Edwards put it, who went along for most of the journey with me. And it works. The gentle way he could create characters, elide the biggest events and focus on the smaller build ups and aftereffects, all while quietly inviting the audience to just sit down on the tatami mat like a family member creates this world of a not quite real Tokyo, too nice to be reality, but full of true human emotions that are there for those willing to sit on that tatami.

And I think you should.

Sitting Down on the Tatami

So, imagine for a moment that I've intrigued you. Where do you begin? Start with his most famous film, Tokyo Story. The story of two elderly parents who try and spend a week with their two children and their deceased son's wife in the eponymous city, getting shuffled around because life happens, never really connecting with their children but being understanding about it the whole time. It's a marvelous film, but you have to be ready for the rhythms of Ozu's cinematic grammar.

And that's why I start with such hesitation. How many will say, "Sure, I'll try this," see a five-minute long scene of two old people packing, and just be turned off because "nothing's happening"? I wish I had the authority to just say, "Watch this," and people would be patient with whatever I recommended, but that's not the case. You're more likely to dismiss my recommendations blind than accept them, so I gingerly describe what Ozu's films are like, how they work, why they came about, and hope that those of you who read through and feel like there's something there in Ozu's work that interests you won't be surprised when you do finally try.

That's not going to be all of you. I doubt it's most of you. Heck, I doubt it's a significant portion of you. However, for those few of you who do think that Ozu's music boxes of repeating characters, actors, and plots sounds intriguing and have never discovered it, well...start with Tokyo Story. The whole thing is on archive.org for some reason. Also, my personal favorite Ozu film, Late Autumn, is also available on archive.org in full.

And for those interested in Schrader's take on Ozu, there's the book itself, Transcendental Style in Film, which you can find anywhere to buy, but there's also this 26-minute long video of him summarizing the new introduction he wrote a few years ago to the book he wrote in his youth in the early 70s. The book is an academic text, but I found it engrossing and interesting.

Another Voice

Mark Andrew Edwards decided to go along on this journey with me, watching as much of Ozu's filmography as he could, and he ended up writing an essay of his own. Mark and I don't always agree on movies, and there were Ozu films that we found some distance between ourselves on, but Ozu's films obviously ended up meaning something to him as well. So, I want to end with an observation from his essay (which you can read in full here):

"But we are in the room, an invisible ghost, a trusted friend of the family, allowed to see everything, knowing we aren't there to interfere, but just share and learn, maybe to commemorate, maybe to celebrate silently with them. And sometimes, we leave the characters and contemplate the natural world outside, drifting along with the wind memorably in one instance. His films aren't in a hurry to hustle us outside or on to the next spectacle. There's no big drama, just little dramas, of life. Life moving on. Ozu stories don't end, the camera is just turned off. All these characters are going on, living their life even after our observation ends."

Movies of Today

Opening in Theaters:

I Know What You Did Last Summer

Eddington

Smurfs

Movies I Saw This Fortnight:

Late Autumn (Rating 4/4) Full Review "The combination of light comedy and clear-eyed character work that drives the drama creates this emotional impact and catharsis by the end that carries me for the final half-hour. It's subtle, deeply moving, funny, a remarkable film. It's one of the greats." [The Criterion Channel]

The End of Summer (Rating 3/4) Full Review "So, it's good. Ozu was simply far too skilled at this point to make anything less than that. However, this feels like a film bred from something other than his desire to refine his technique, an attempt to take advantage of a unique professional situation rather than a story he needed to tell once more, though it does share a lot of the same motifs." [The Criterion Channel]

An Autumn Afternoon (Rating 4/4) Full Review "I loved this film. Absolutely loved it. If Late Autumn hadn't hit me so hard, I'd be calling this Ozu's best work in a body of work that includes Tokyo Story. And that's why I wanted Ozu to live and work another 30 years. He could make the same story of a parent giving away a daughter repeatedly forever, and I'd watch and enjoy them forever." [The Criterion Channel]

The Young Stranger (Rating 4/4) Full Review "It doesn't surprise me that no one searches out Frankenheimer's first film, a small family drama he made in the middle of his television career before Birdman of Alcatraz with no movie stars and not at all genre related. But, I think that should be fixed." [YouTube]

The Young Savages (Rating 2.5/4) Full Review "There's a lot to admire in the first two-thirds of the film. The last third, though, simply fumbles things uncompellingly with a combination of bad courtroom antics and intentional obfuscation." [Prime]

Birdman of Alcatraz (Rating 3/4) Full Review "It's how the film can never quite separate itself from the fact that it's almost as much an issue piece as it is a human interest piece. However, the human interest side wins out in the end. It's a nice, easy little fantasy about the strength of the human heart, and not much else." [YouTube]

Seven Days in May (Rating 4/4) Full Review "It exists in something of a fantasy world where the military would orchestrate a coup without the CIA, the USSR is remotely trustworthy, and a disarmament treaty had any chance at all of passing the Senate in the early 60s. Still, within that fantasy world, this is a banger of a thriller. Dr. Strangelove had a better handle on the real world situation, though." [Personal Collection]

The Train (Rating 4/4) Full Review "And that makes The Train a complete package of a film. Entertaining on the surface but thoughtful just underneath, expertly filmed and wonderfully performed, especially by Lancaster and Scofield, it's John Frankenheimer's greatest achievement." [Personal Collection]

Contact

Email any suggestions or questions to thejamesmadison.aos at symbol gmail dot com.

I've also archived all the old posts here, by request. I'll add new posts a week after they originally post at the HQ.

My next post will be on 8/9, and it will be about ___.

Recent Comments

SkyNet:

"

I read that over 80 percent in AI assisted surge ..."

fd: ""Tomorrow, building codes will standardize plumbin ..."

Piper: "I still want a Tesla Optimus to fold my laundry, t ..."

Rick T: "All he is doing is feeding the hype machine trying ..."

Mae West: "AI could never have taken my place. ..."

Ian S.: "Microsoft is full of shit. Every time there's a ..."

SciVo: "[i]85 A development that's progressing as fast as ..."

garrett: ">>AI asks a bunch of questions and then recommends ..."

Dave: "[i]I don't know if I'm ready to trust AI with anyt ..."

Unknown Drip Under Pressure: "[i]Most of the jobs taken will be Cush jobs libera ..."

banana Dream: "It still pisses me off that my phone's clankers wo ..."

mrp: " AI won't fix a clogged sewer drain at 3 AM on a S ..."

fd: ""Tomorrow, building codes will standardize plumbin ..."

Piper: "I still want a Tesla Optimus to fold my laundry, t ..."

Rick T: "All he is doing is feeding the hype machine trying ..."

Mae West: "AI could never have taken my place. ..."

Ian S.: "Microsoft is full of shit. Every time there's a ..."

SciVo: "[i]85 A development that's progressing as fast as ..."

garrett: ">>AI asks a bunch of questions and then recommends ..."

Dave: "[i]I don't know if I'm ready to trust AI with anyt ..."

Unknown Drip Under Pressure: "[i]Most of the jobs taken will be Cush jobs libera ..."

banana Dream: "It still pisses me off that my phone's clankers wo ..."

mrp: " AI won't fix a clogged sewer drain at 3 AM on a S ..."

Recent Entries

Antifa-Affiliated Group Stomps a Normal Peaceful Student to Death in Lyon, France

Microsoft AI CEO: Most White-Collar Jobs Will be "Automated by AI" Within Ten Years

I Mean, Within Twelve to Eighteen Months

Stephen Colbert Involved in Yet Another Leftwing Propaganda Hoax

Jesse Jackson Departs This Mortal Coil to Shake-Down Heaven and Demand God Give $300,000 p.a. Jobs to His Retarded Cousins and Staffers

Palestinian Activist in NYC Calls for Dogs to be Banned as "Indoor Pets" -- No Longer Permitted Inside People's Private Apartments -- Because They are "Unislamic" and "Dirty"

Yet Another "Trans" Mass Shooting the Media Will Pretend Was Perpetrated by a "Woman"

Operation PROTECT DONKEY-CHOMPERS: Leftwing Propaganda Media Goes Into Overdrive Claiming That AOC's Embarrassingly Incompetent Performance At Munich Was Akshually "Cogent" and Critics Are Just "Microscopically Dissecting" Her "Message"

The Morning Rant

Mid-Morning Art Thread

The Morning Report — 2/17/26

Microsoft AI CEO: Most White-Collar Jobs Will be "Automated by AI" Within Ten Years

I Mean, Within Twelve to Eighteen Months

Stephen Colbert Involved in Yet Another Leftwing Propaganda Hoax

Jesse Jackson Departs This Mortal Coil to Shake-Down Heaven and Demand God Give $300,000 p.a. Jobs to His Retarded Cousins and Staffers

Palestinian Activist in NYC Calls for Dogs to be Banned as "Indoor Pets" -- No Longer Permitted Inside People's Private Apartments -- Because They are "Unislamic" and "Dirty"

Yet Another "Trans" Mass Shooting the Media Will Pretend Was Perpetrated by a "Woman"

Operation PROTECT DONKEY-CHOMPERS: Leftwing Propaganda Media Goes Into Overdrive Claiming That AOC's Embarrassingly Incompetent Performance At Munich Was Akshually "Cogent" and Critics Are Just "Microscopically Dissecting" Her "Message"

The Morning Rant

Mid-Morning Art Thread

The Morning Report — 2/17/26

Search

Polls! Polls! Polls!

Frequently Asked Questions

The (Almost) Complete Paul Anka Integrity Kick

Primary Document: The Audio

Paul Anka Haiku Contest Announcement

Integrity SAT's: Entrance Exam for Paul Anka's Band

AllahPundit's Paul Anka 45's Collection

AnkaPundit: Paul Anka Takes Over the Site for a Weekend (Continues through to Monday's postings)

George Bush Slices Don Rumsfeld Like an F*ckin' Hammer

Paul Anka Haiku Contest Announcement

Integrity SAT's: Entrance Exam for Paul Anka's Band

AllahPundit's Paul Anka 45's Collection

AnkaPundit: Paul Anka Takes Over the Site for a Weekend (Continues through to Monday's postings)

George Bush Slices Don Rumsfeld Like an F*ckin' Hammer

Top Top Tens

Democratic Forays into Erotica

New Shows On Gore's DNC/MTV Network

Nicknames for Potatoes, By People Who Really Hate Potatoes

Star Wars Euphemisms for Self-Abuse

Signs You're at an Iraqi "Wedding Party"

Signs Your Clown Has Gone Bad

Signs That You, Geroge Michael, Should Probably Just Give It Up

Signs of Hip-Hop Influence on John Kerry

NYT Headlines Spinning Bush's Jobs Boom

Things People Are More Likely to Say Than "Did You Hear What Al Franken Said Yesterday?"

Signs that Paul Krugman Has Lost His Frickin' Mind

All-Time Best NBA Players, According to Senator Robert Byrd

Other Bad Things About the Jews, According to the Koran

Signs That David Letterman Just Doesn't Care Anymore

Examples of Bob Kerrey's Insufferable Racial Jackassery

Signs Andy Rooney Is Going Senile

Other Judgments Dick Clarke Made About Condi Rice Based on Her Appearance

Collective Names for Groups of People

John Kerry's Other Vietnam Super-Pets

Cool Things About the XM8 Assault Rifle

Media-Approved Facts About the Democrat Spy

Changes to Make Christianity More "Inclusive"

Secret John Kerry Senatorial Accomplishments

John Edwards Campaign Excuses

John Kerry Pick-Up Lines

Changes Liberal Senator George Michell Will Make at Disney

Torments in Dog-Hell

Greatest Hitjobs

The Ace of Spades HQ Sex-for-Money Skankathon

A D&D Guide to the Democratic Candidates

Margaret Cho: Just Not Funny

More Margaret Cho Abuse

Margaret Cho: Still Not Funny

Iraqi Prisoner Claims He Was Raped... By Woman

Wonkette Announces "Morning Zoo" Format

John Kerry's "Plan" Causes Surrender of Moqtada al-Sadr's Militia

World Muslim Leaders Apologize for Nick Berg's Beheading

Michael Moore Goes on Lunchtime Manhattan Death-Spree

Milestone: Oliver Willis Posts 400th "Fake News Article" Referencing Britney Spears

Liberal Economists Rue a "New Decade of Greed"

Artificial Insouciance: Maureen Dowd's Word Processor Revolts Against Her Numbing Imbecility

Intelligence Officials Eye Blogs for Tips

They Done Found Us Out, Cletus: Intrepid Internet Detective Figures Out Our Master Plan

Shock: Josh Marshall Almost Mentions Sarin Discovery in Iraq

Leather-Clad Biker Freaks Terrorize Australian Town

When Clinton Was President, Torture Was Cool

What Wonkette Means When She Explains What Tina Brown Means

Wonkette's Stand-Up Act

Wankette HQ Gay-Rumors Du Jour

Here's What's Bugging Me: Goose and Slider

My Own Micah Wright Style Confession of Dishonesty

Outraged "Conservatives" React to the FMA

An On-Line Impression of Dennis Miller Having Sex with a Kodiak Bear

The Story the Rightwing Media Refuses to Report!

Our Lunch with David "Glengarry Glen Ross" Mamet

The House of Love: Paul Krugman

A Michael Moore Mystery (TM)

The Dowd-O-Matic!

Liberal Consistency and Other Myths

Kepler's Laws of Liberal Media Bias

John Kerry-- The Splunge! Candidate

"Divisive" Politics & "Attacks on Patriotism" (very long)

The Donkey ("The Raven" parody)